The death of the Sustainability professional (as we know it)

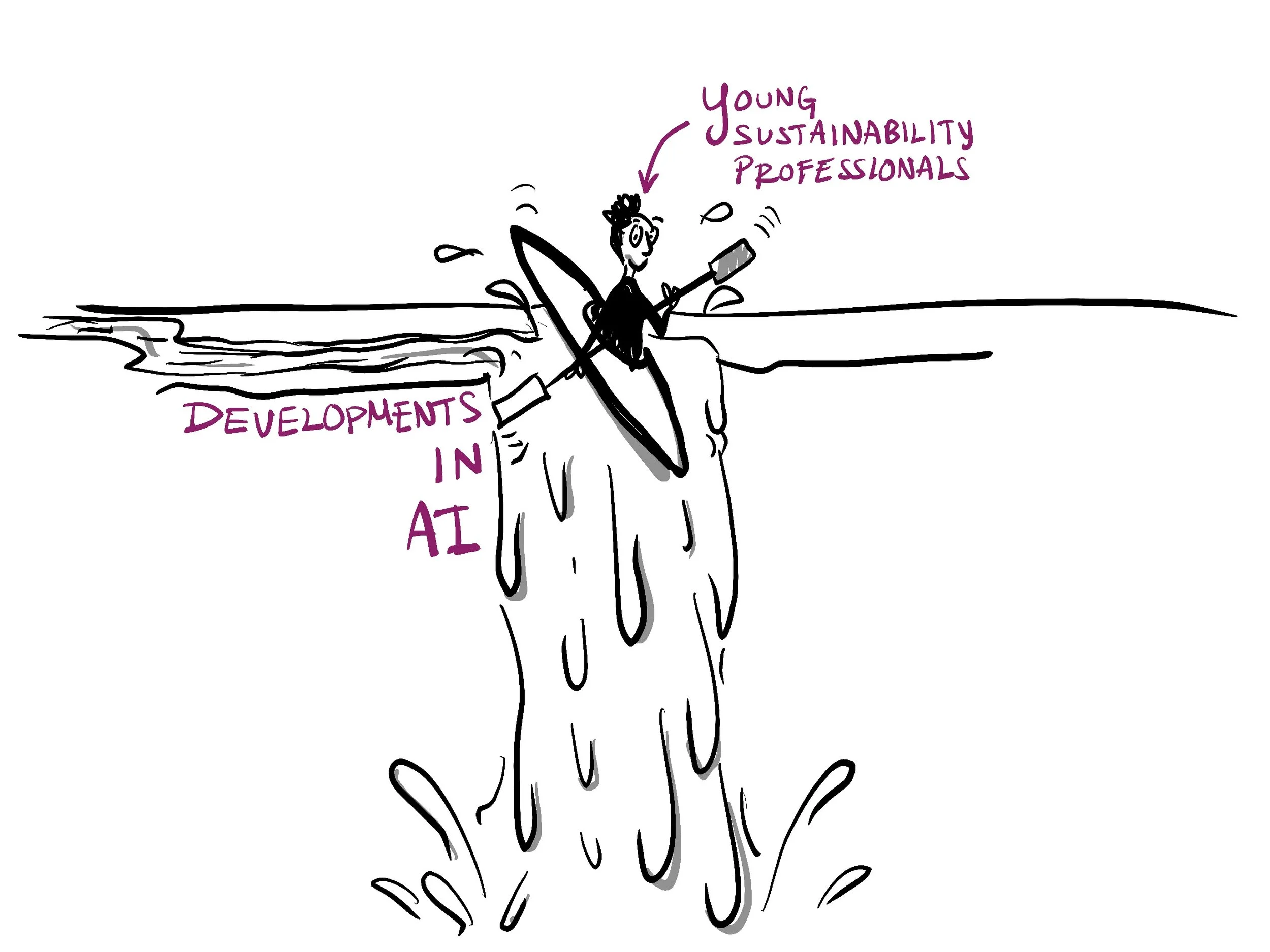

It does feel a bit like this, to be honest.

Something is shifting in our field, and many of us can feel it, even if we can’t yet name it. Sustainability assessment is standing at the edge of a transformation that will likely redefine what we do, how we work, and perhaps even who counts as a “sustainability professional”, especially as it relates to sustainability and circularity assessment.

For years, our expertise has been the often complex and definitely demanding work of collecting data, running and verifying LCA models, comparing scenarios, and (hopefully) help industry make sense of environmental complexity. But most of this work is increasingly within reach of AI systems improving far faster than expected. I’m not saying AI will replace everything; I’m saying it no longer feels unthinkable that the core analytical work will be automated sooner than we imagined.

If AI increasingly stands on the bridge between data and decisions, automating much of what practitioners historically handled manually, then our profession faces a branching moment. For what I see so far, one option is to move upstream, deeper into technical modelling or environmental data science. Another is to move downstream into operationalization: taking results largely at (critically examined) face value and focusing on redesign, experimentation, and real-world implementation. And a third path is to remain in the middle, as some kind of "AI-augmented" environmental analyst; people who understand both environmental mechanisms and the data logic behind automated analyses.

I find myself gravitating toward the downstream territory, where fields like sustainability transitions, implementation science, design for sustainability, and circular economy innovation have long recognized that numbers alone do not shift systems. People, institutions, technologies, and incentives do. Downstream work might mean leveraging our expertise differently: perhaps framing systems and mapping how decisions ripple across supply chains, exploring and prototyping redesign options or perform activities we can’t yet even see.

Of course, I may be wrong. I am writing from inside the fog, from a place of intuition and unease. This uncertainty isn’t abstract; it reaches directly into our own careers (and our sense of self). A certain version of us is ending, and our identity will not remain untouched.

Think about the map-maker. For a long time, cartographers measured landscapes and drew the world by hand. Then satellites, GPS, and GIS arrived. The job “cartographer” largely disappeared. The sector did not vanish; it dispersed into geospatial science, planning, logistics, modelling, and countless new specialties. The craft died, but the field expanded. I do wonder if it was those same cartographers the ones who took on the new jobs, or people form emerging study fields.

Sustainability assessment may be entering a similar inflection point. If AI automates the mechanical parts of our work, it forces us to confront a question we, otherwise, might prefer to avoid: What is our deepest contribution? Where can we create the most impact?

LCA practitioners as cartographers of the natural world.

Whether we frame this moment as collapse or evolution is, in many ways, up to us.

And that’s the strange, uncomfortable, hopeful thing:

If our profession, as we know it, dies, we have the opportunity to re-draw our identity.

I don’t know what the new version will look like. None of us do. But I much rather take the steering wheel in my own hands, than try to look the other way.

How not to embrace a transition…